PHIL 3310. Exploring the philosophical, ethical, spiritual, existential, social, and personal implications of a godless universe, and supporting their study at Middle Tennessee State University & beyond.

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Blog Asst pt 2 (and 3?) The Spirituality of Power (non vice-versa)

In this installment, I shall tackle the notion of power in regards to the faithless - those who do not readily worship, or even acknowledge such a divine power, people such as myself, and majority of the class.

If you do not follow divine command theory - that is, taking your orders from a higher power, you're rationalizing your morality out of some ethically archetypal school of thought, like Kantian judgement, Niccomachean Ethics, Ethical Egoism, etc. However, each of these draws its conclusions based on some measurement of power.

Take Ethical Egoism or Utilitarianism for example. Both ultimately mandate to do what is in the "best interest."

In Ethical Egoism's case, it charges the actor to do what is in one's own best interest. "I can lie, cheat, or steal, so long as I come out on top. It's not a good idea to do this though, because if I get caught, and I probably will, then everyone will know I am a less than reputable chap, and the outcome will be negative for me."

In Utilitarianism's case, one does what is in the best interest of a whole, or a greater good. A fantastic example of utilitarianism can be found in Alan Moore's "Watchmen"(If you haven't read the graphic novel, or at least seen the movie, I recommend it, exclusively for the ethical metaphors so well constructed throughout). In it, Ozzymandias, the alleged "smartest man in the world," devises a plot to kill millions of New Yorkers with an incredibly complicated scientific device, which the world blames on either Aliens (if you read the comic) or Dr. Manhattan, the resident demigod of the United States (if you watched the movie). The act in and of itself was carried out in lieu of an inevitable nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union, but the sudden disaster was enough to unite the two superpowers in a worldwide utopia, out of fear of some far greater, yet completely nonexistent threat. Ozzymandias rationalizes this as "killing millions to save billions" - Utilitarianism at its finest.

Both of these however, rest entirely on one's power - one's ability to do. Both are consequentialist schools of logic; they require that rational action first follows the consideration of the consequences. Considering is a form of doing. Therefore, the power to consider the consequences of your actions is a form of power.

In Kantian ethics, one derives what is ethical from rationally considering one's duties, or looking at the laws of the society at large. If there aren't rules to cover the situation, imagine the action universalized, and see if it makes any sense to live in that kind of world. For example - murder.

Imagine a world where the act of murder is universalized. Human life would quickly extinguish itself in a massive, self imposed apocalypse of the most gruesome proportions. Murder is clearly not ethical. Imagine theft, as well. If everyone were a thief, trust would be out of the question, and entire economies would collapse because the very basis of exchange presumes trust between the buyer and seller. Therefore theft is not ethical. Here again, we witness power. Not only the power to consider circumstances, but the power to create and universalize a series of events on a grand scale to achieve such considerations. One might even go so far as to say that by universalizing instances of an action to determine its morality, we are acting as gods of our own imagination - exercising our power over it to do whatever we please in order to experiment with our own rational decision making process.

Regardless, power is the key factor here. If we hadn't the power to do these things, we would be without the ability to reason ethically, if not the ability to reason at all, and society would either cease to function altogether, or divine command theorists would be the only people on earth with any assertive idea as to what was to be done about anything.

I would venture to say that most anyone engages in ethical reasoning without a god is certainly proud of it, otherwise they simply wouldn't do it. There is an inherent sense of accomplishment in that you know what is right or wrong without being told explicitly what is right or wrong, but being able to determine it for yourself. It is enriching and empowering. There is no subdued voice in the back of your mind begging the question muttering "but why did God say that x was wrong in the first place? All you know is that he said it was wrong." On the contrary, you usually know what is wrong and why, exactly why, and you can really engage discussion with someone about the reasons of it for hours, if you felt like it.

The feeling that comes with this power, I argue is in and of itself spiritual. When I lost my faith during my adolescence, I felt as though I were achieving some level of transcendence - critical thinking, rather than blind faith- being what a divine being would employ to determine what is right and wrong before dumbing it down and mandating it to its subjects. I'm sure that many will agree that if there is anything divine in humanity, it is the power to make rational decisions on a great many matters, and reason among one another.

To conclude (how I originally intended in a third blog post, but found unnecessary halfway through writing this), the faithful worships the power of their respective divine entity, not the entity itself. The faithless do not worship, per se, but we all hold in great esteem our powers of reason, deduction, creation, and action. They are powers that have taken us to strange continents, the moon, and we later hope to employ them to take us to other worlds and galaxies beyond. Most importantly, however, they give us the power to traverse the distances between one another, and we are well aware of it.

These two very opposed representations of reality, one in which a divine power is what manifests our reality, and we barter with it for favorable outcomes - and the other is one in which we are the only sentient things to be held accountable for the way things are both rest exclusively on the very broad and vibrant idea of power. A concept completely and utterly intangible, but at the same time unequivocally existent.

Thomas Jefferson Quote

Here's a little pep talk from our buddy Tom:

"Ridicule is the only weapon which can be used against unintelligible propositions. Ideas must be distinct before reason can act upon them; and no man ever had a distinct idea of the trinity. It is the mere Abracadabra of the mountebanks calling themselves the priests of Jesus.”

― Thomas Jefferson

I'll miss you guys; see you next Tuesday.

Berry lecture

There's another BERRY LECTURE coming up Thursday night, this one by Reasonable Atheism co-author Rob Talisse ("Must Life Be Tragic?"). Lecture begins at 7:30 in Furman 114, but come early for booze & informal conversation.

==

Also, on Friday at 3:15 pm: Vandy's philosophy department hosts a colloquium featuring Jill Stauffer of Haverford College, in Furman Hall 109. Reception to follow.

Ethical Loneliness: Forgiveness, Resentment, and Recovery

Abstract:

Atheism and Agnosticism: Nothing to See Here....Midterm Blog Project Post #3

First, a quick review. In my first two posts, I attempted to come to some reasonable definitions for both atheism and agnosticism. For atheism, I like “a lack of belief in the existence of God or gods.” For agnosticism, I settled on “the view that the truth value of certain claims—especially claims about the existence or non-existence of any deity, but also other religious and metaphysical claims—is unknown or unknowable.” Putting these two definitions side by side should give the reader some rather unsurprising insight into the position that I intend to illuminate in the course of this essay: properly defined, atheism and agnosticism should not ever be in conflict. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that should you find yourself thinking that the two stances are at odds, you are “doing it wrong.” In other words, you are either adopting an unjustified definition, or you are carrying some bias, or you are simply using words incorrectly. To put it yet another way: if you accept the two definitions above and still think that atheism and agnosticism are incompatible, you have some explaining to do.

Maybe a few examples of how belief and knowledge can coexist would be helpful. Let’s look at some mundane and not so mundane statements, bearing in mind the following conditions:

1. Absolute knowledge is in all likelihood impossible, and is therefore not a reasonable standard.

2. It is possible to know the status of one’s own beliefs.

3. The presence of a belief precludes the absence of that belief, and vice versa. In other words, you either believe X or you lack a belief in X. If you lack a belief in X, then you do not believe in X (either actively or passively.)

4. The burden of proof rests with the party making any particular claim (with respect to #1.)

Now that we’ve laid the groundwork, on to the examples! Consider the following statements:

“I sometimes feel nostalgic.”

“I am not right handed.”

“Australia is a continent in the southern hemisphere.”

“The sun is an enormous cloud of hydrogen undergoing sustained gravitational collapse offset by nuclear fusion.”

“I love my girlfriend, and she loves me.”

“I love God, and God loves me.”

These statements represent a broad cross section of the kinds of statements that it is possible to make regarding belief and knowledge, running the gamut from subjective first person claims to objective claims about the natural (and supernatural) world. Let’s look at each one in turn.

When I make a claim about my own state of mind, this can be thought of as an objective claim about a subjective state (assuming that I am not lying.) Perhaps someday, neuroscience will allow us to somehow verify these claims in a way that we currently cannot. But for now, people have to be relied upon to report their own mental state, for there simply is no other way to gain access to it. In other words, to say that I sometimes feel nostalgic is for me to know that I am sometimes nostalgic. Belief doesn’t enter into the matter. The person evaluating my claim, however, is presented with a different situation. They must decide whether or not it is justified to believe that I do indeed sometimes feel nostalgic. If this evaluator was especially motivated, they might interview me, observe my actions for some period of time, or ask questions of my friends and family. But all of this seems rather involved an unnecessary, does it not? In general, people can be relied upon to know what they feel, think, and believe about their own state of mind. And as long as we have no reason to think that the person in question is being dishonest, we can be justified in believing their claim.

My claim about whether or not I am right handed is amenable to a higher degree of observable verification. By definition, to be right or left handed means that you are more proficient using one hand over the other. This makes it a rather simple matter to test this claim, by experiment and observation. If these observations bear out my claim, then it would be reasonable to believe it. Note that it might still be possible for the underlying truth of my claim to be false, however. I might actually be ambidextrous, and capable of hiding this fact from direct observation. So while it would certainly be possible for a person to believe my claim of not being right handed, this believe might be based on flawed observational knowledge.

Once we move to the continental scale, things become even easier. Yes, the Earth is a big place, but not that big. In the age of airplanes, cruise ships, GPS satellites, and Australians (!), it is simply not reasonable to hold any dissenting opinions about the status of Australia’s existence or relative position. There is a plethora of evidence attesting to both, and my beliefs about it are well informed by all sorts of mutually buttressing knowledge. Is it possible that we have, all of us, been deceived in some way about these seemingly indisputable facts about Australia? That is one awfully heavy burden of proof to bear, and I can’t imagine how it could be the case. But, even in this extreme case, some vanishingly small sliver of agnosticism might be (barely) reasonably entertained. But honestly, we would have to be talking about a Matrix or Truman Show level event. That is an awful lot of wool to be pulled over an awful lot of eyes. In other words, I’m not losing any sleep over the possibility.

The sun is a very similar case, though it is different in a few crucial ways. We cannot walk on the surface of the sun, obviously. We can’t talk to people who live there, or to anyone who has ever visited. We are forced to rely on the tools of science to extend our senses beyond what we are used to dealing with. We use spectrographs to peer into the invisible parts of light that our eyes cannot see. We propel spacecraft into orbit around the sun, studded with sensors that relay back enormous amounts of data that scientists then interpret. We use telescopes to peer out into the vast reaches of space, capturing other suns in various stages of birth, life, and death. Taken as a whole, these lines of evidence lead to a robust and growing body of knowledge about our sun. Using this knowledge, scientists can make accurate predictions about solar storms and sunspot cycles, centuries and even millennia into the future. With a simple almanac, anyone that cares to can judge for themselves the accuracy of this knowledge. Again, none of this precludes the possibility that we cannot be mistaken about particulars, or misinterpret specific pieces of data. In fact, this will surely be the case at some point. What it does indicate, however, is that our beliefs about the sun are very well informed by verifiable knowledge.

I love my girlfriend, and she loves me. Simple, right? As we have already established, I can be relied upon to be the judge of my own thoughts, feelings, and beliefs. The thoughts of my girlfriend can be ascertained by her spoken words, her unspoken communications, and by judging her actions to be consistent or inconsistent with what it means to love someone (using some agreed upon definition.) This is all well and good, of course. I take all of these bits of data into account, and I form a belief (based on my knowledge of the perceived facts) that my girlfriend does indeed love me. Is possible that my belief is incorrect, that is to say that it is actually inconsistent with the actual facts? Yes, such a situation is possible (or at least conceivable.) The movie Total Recall is the example that immediately springs to my mind. The protagonist had suffered the loss of specific memories from his past, and found himself in the position of having had these missing memories replaced with false ones. His wife, who professed her love for him, was actually a double agent only acting as though she loved him. Thus, our hero found himself in a situation where his beliefs were not consistent with reality. Once the deception was revealed, he was free to revise his beliefs in order to bring them into line with this new knowledge. So to recap, a person can sincerely believe something, and know that they believe it, even if their belief is based on incorrect knowledge. Based on his knowledge of the world around him, the Total Recall protagonist was justified in believing that his wife loved him. But this belief couldn’t be reconciled with reality, once the truth was revealed.

Our final example is where things get really sketchy. At first blush, it looks to be very similar to the previous example, mainly owing to similarities in sentence structure. Our first problem, however, lies with the object of my love. When the object is my girlfriend, everything is peachy. She is a real person, just like me, available for observation, experimentation, inspection (careful, she bites), and conversation. In other words, the existence of my girlfriend is such that she is a valid object to be loved. God does not enjoy the same status of existence. He (it, she, they?) is not available for observation, experimentation, inspection, or conversation.

Maybe I am referring to God as a concept, like freedom or democracy? Certainly both of these things can be and have been loved by countless people over the years. But we cannot reach a reasonable agreement on what the concept of God is, not like we can with concepts like freedom. And to further screw the “God is a concept” pooch, how can you be loved in return by a concept? Someone is simply not using words correctly. Instead, they are using unverified and unverifiable statements of anecdotal and authoritative dogma that have been passed down from antiquity to construct their beliefs. Everything we “know” about God comes to us through indirect channels. We are unable to “go to the source”, as it were. Thus, we have no reliable knowledge about the person (or concept) of God. Therefore, any beliefs that a person has about God must necessarily be based on exceedingly weak knowledge.

The real rub, as we all know, comes in the unfalsifiable nature of knowledge claims about God. How can a person ever be proven to be wrong about their beliefs about God? They simply can’t, not as long as they are determined to believe things for bad reasons. Unlike our Total Recall protagonist, “God” could only ever be outed as a ruse after the person’s death. And that is just a little too late for our purposes.

So, where does that leave us? Good question, because we have drifted far afield of where we started. Let me explain. No, there is too much. Let me sum up.

1. People form beliefs based on observed states of the world, which we call knowledge.

2. Nobody has perfect knowledge (you can’t prove a negative.)

3. It is possible to believe something, and have that belief be based on incorrect knowledge.

4. The best we can hope for is to remain open to new evidence, and adjust our beliefs accordingly.

Therefore, I can make the following statements:

I don’t believe in God, but I am always open to new evidence.

I believe that there is no God, but I don’t know that he doesn’t exist.

I don’t believe that God exists, and I live my life as though he doesn’t.

I can know what I believe, while also knowing that my beliefs are based on provisional knowledge.

I am an agnostic atheist.

Shermer on Teaching Allah and Xenu in Indiana

Last month, the Indiana State Senate approved a bill that would allow public school science teachers to include religious explanations for the origin of life in their classes. If Senate Bill 89 is approved by the state’s House its co-sponsor, Speaker of the House Dennis Kruse, hopes that this will open the door for the teaching of “creation-science” as a challenge to the theory of evolution, which he characterized as a “Johnny-come-lately” theory compared to the millennia-old creation story in Genesis: “I believe in creation and I believe it deserves to be taught in our public schools.” (continues...) -Michael Shermer

'via Blog this'

Midterm Project--Post 1 & 2: God and Morality

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

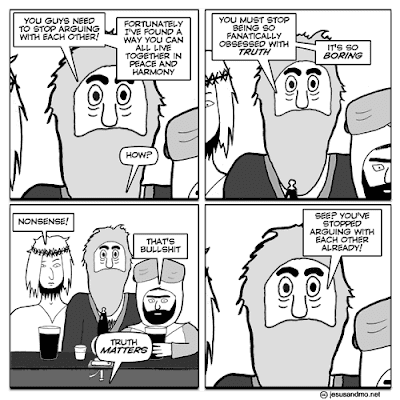

A few thoughts from the Philosoraptor

Take a peek inside the vortex that is my final blog installment....

A Philosophical Perspective on a Neuroscientific Perspective

Here is a link that delves more into the Philosophical aspects of what Ben and I talked about today. It's from the BBC, so it's replete with fancy British accents. I like to listen to British people wax philosophic when trying to sleep sometimes, so, maybe try that.

Thank you all so much for your attention and participation today. Hope you enjoyed it.

JT Eberhard engages Alain de Botton. Carnage ensues.

Talisse at Vandy

There's another BERRY LECTURE coming up Thursday night, this one by Reasonable Atheism co-author Rob Talisse ("Must Life Be Tragic?"). Lecture begins at 7:30 in Furman 114, but come early for booze & informal conversation.

Group 3: Confessions of a Kindergarten Leper

Fact Q: What is the name given to the event that fundamentalist christians believe will procede the end of the world, where all true believers will be "taken up" into the clouds to be with Jesus?

A: The Rapture

Emma Tom

Q: What did Emma's teacher tell her that kids who don't believe in God get?

A: leprosy

Exam Questions!!

1. What is the main problem with the cosmological argument for the existence of God?

a. Which god is it?

b. Who caused God?

c. Gods don’t exist.

d. People are just mad at God.

2. Who first articulated the ontological argument for God?

a. Saint Anselm

b. Saint Augustine

c. Deepak Chopra

d. Alexander the Great

3. What book undermined the argument from design?

a. On Origin of Species by Charles Darwin

b. The Republic by Plato

c. The Meaning of Relativity by Albert Einstein

d. The Flintstones by Hanna-Barbera Productions

4. Who made the argument from moral truth (the problem of evil) famous?

a. Christopher Hitchens

b. Plato in Euthyphro

c. Saint Augustine in Confessions

d. William James in The Will to Believe

5. The argument from pragmatism is well articulated in what author’s work?

a. On Origin of Species by Charles Darwin

b. Euthyphro by Plato

c. The Will to Believe by William James

d. The Tractatus by Ludwig Wittgenstein

e. None of the above

6. What is the essence of the teleological argument?

a. God so loved the world he gave his only begotten son.

b. God telepathically commanded pairs of animals to get on the ark.

c. The world gives the illusion of design so it had to have an intelligent designer

d. Nothing greater than God can be conceived

7. Julian Baggini in Atheism: A Very Short Introduction argues for:

a. Negative atheism

b. Positive atheism and naturalism

c. Stridency

d. Belief in God is a “properly basic belief.”

8. In Louise Antony’s piece commencing Philosophers without Gods, she says the most important thing that non-believes loose is:

a. The guarantee of redemption

b. Killing in the name of God

c. Telling non-believer’s children they’ll burn in hell

d. Petitionary prayer

9. One of the main points in Walter Sinnott-Armstrong’s Overcoming Christianity is that people many people hold certain religious beliefs simply because:

a. Their beliefs are true

b. They have thought through their beliefs

c. They will be killed or ostracized if they leave their faith

d. They accept religious traditions without questioning

10. Who recently proposed the Temple of Atheism?

a. Richard Dawkins

b. Christopher Hitchens

c. Deepak Chopra

d. Alain de Botton

e. Sam Harris

11. Clifford's "Ethics of Belief" and the wrongness of believing without evidence is now being popularized by what evolutionary biologist?

A: Richard Dawkins

12. What, according to Clark, defines the worldview of"naturalism"?

A: disbelief in a creator, a corollary of the rationally defensible claim that nature is all there is

13. What Christian museum displays “The Tree of Evolutionism”? this tree claims that everything evil stems from the teaching of the theory of evolution. Including: pornography, racism, sex education, feminism, drug abuse, Nazism, and humanism, etc.

A: The Institute for Creation Research Museum in Santee, California

14. Who is the quote in the title ("If God is dead, then everything is permitted") from?

A: Dostoyevsky

15. What is the difference between onto-religion/theology and "expressive" religion/theology?

A: Onto-religion/theology makes statements that are factual claims about how the world "is"

16. What does Dennett suggest is an awesome question to keep asking oneself to guard against faith, tradition, and dogma of all types?

Answer: "What if I'm wrong?"

17. What was the name of Aristotle’s most famous work on ethics?

A: Nicomachean Ethics

18. In Dostoevsky's novel, The Brothers Karamazov, what is Ivan's maxim?

A: If there is no god, then anything is permitted.

19. What is the title of Pascal's work that includes his infamous wager?

A: Pensées

20. 'In Plato's dialogue "Euthyphro", who is Euthyphro being questioned by on the nature of holiness?

A: Socrates!

21. What is the Divine Command Theory?

22. According to Baggini how can atheists have morals if God does not exist?

23. Who said he goes "one god further" than those who reject Zeus, Apollo, et al?

A. Richard Dawkins

24. John Harris says respect for persons does not entail respect for ______.

A. Beliefs

25. Which atheist has been repeatedly billed as "the most hated women in America?"

A. Madalyn Murray O'Hair.

26. (T/F) The "greater good" defense is one of the more frequent objections put forward against the Euthyphro dilemma.

A. True.

27. F.H. Bradley famously remarked that "_______ is the finding of bad reasons for what we believe on instinct."

A. Metaphysics.

28. Plato says that philosophy begins in ________.

A. Wonder.

29. Who are the Four Horsemen of New Atheism?

A. Richard Dawkins, Dan Dennett, Sam Harris, and Hitch.

30. Who said "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death

your right to say it?"

A. Voltaire

31. God is ________.

A. ???

Monday, February 27, 2012

Group 1: Shermer - How to Think About God

Reason Rally, March 24 2012

Next (re-posted)

T 28 Blackford (Shermer, Randi, Tom, Kitcher, Edis).We'll have more presentations on Tuesday: Ben & Steven, Religion & Neuroscience; Meghan, Parenting Beyond Belief OR Matthew, tba...

Syllabus said the exam's on Tuesday, but that's wrong. It'll be Thursday.

Th 1 Exam #1, re-group, Vote on additional textOur voting options will include "Potluck": instead of a single additional text for those April dates, we could just have everybody "bring their own" whatever (book, article, video, documentary,...) and comment on it. But if you have candidate texts you want us to consider, post your nominations before Thursday.

Don't know if we need to re-group. But we can, if you're tired of always getting stuck with the 2d, 3d (etc.) essay.

Remember, if you're doing blog posts for your midterm report: the last installments should be up by next Thursday (1st). Or maybe Friday, if you need just a little more time.

"A Better Life" is photographer Chris Johnson's exciting atheist book project. You can get in on the ground floor...

EXAM UPDATE, Monday morning: I'd asked for more proposed questions for Thursday's exam, but didn't get any over the weekend. So: last call.

There's another BERRY LECTURE coming up Thursday night, this one by Reasonable Atheism co-author Rob Talisse. Lecture begins at 7:30 in Furman 114, but come early for booze & informal conversation.

Following up on our brief discussion of the need for a new Sagan, and whether Tyson's up to the job...

(David suggested somehow making my "next" posts remain in place at the top of the page, so timely bulletins don't get buried beneath the scroll. Does anybody knows how to do that?)