I came across article earlier this week and thought it would be interesting to share here. I've seen many religious people speculate biblical reasons for the occurrence of this pandemic and it's nationally radiating consequences on everyday life.

However, this article investigates an interesting topic: Many godless people still find that things "Happen for a reason" and conclusively asks the question: "What do we learn from times of pestilence?"

Click here to read this article in The Irish Times.

My takeaway is this --

While I find that I identify with a secular way of life, I do also find that I ultimately believe that things happen for a reason; though mostly as a direct consequence from previous actions and not in the spiritual or supernatural nuance that often saturates the conceptualization of events and circumstances being fated, or likewise being rewards or punishments from a higher power.

However, this gets really challenging for me when I put this up against tragedies, and I'm still fine tuning my own belief systems all time. So I would like to know what you all think. But as the aforementioned questions asks, "What do we (society) learn from times of pestilence?"

- Perhaps, in regards to the current pandemic, this can be a reflection of the need for reforms in universal healthcare, as we are seeing first hand that health is directly collective & communal and should not be a class based privilege. A poor person can get a rich person sick, a rich person can get a poor person sick. We're all in this together, but only one side often is provided and afforded the resources they need. Or possibly the need for minimum wage reforms as we are witnessing thousands of "essential employees" risking their health and safety to keep the community functioning at it's most basic levels (keeping grocery stores stocked, for example) all while earning an unlivable wage. The people who have had to keep working, even when they don't want to - because they are not paid enough to afford the luxury of a savings.

Does some good come from most tragedy? Is that not to say that things happen for a reason - so long as we are open to receive it?

PHIL 3310. Exploring the philosophical, ethical, spiritual, existential, social, and personal implications of a godless universe, and supporting their study at Middle Tennessee State University & beyond.

Thursday, April 30, 2020

My Final Post: A Sad Day

I've enjoyed having this outlet during the craziness of this semester, and it's been awesome to interact with all of you. If you see me on campus next semester(Yay to McPhee for his announcement and email) don't hesitate to say hi and tell me a bit about your journey after this class ended. I will also happily accept any book recommendations if you found something particularly interesting.

With that being said, my final tally.

Mar 9-14: Spring Break

Mar 15-21: 2 runs

Mar 22-28: 2 runs + Midterm: 22 runs

Mar 29-Apr4: 2 runs

April 5-11: 2 runs

April 12-18: 2 runs

April 19-24: 2 runs+ Final: 22 runs

April 26-28: 1 run

Total: 53 runs

Thank you for an amazing semester!

With that being said, my final tally.

Mar 9-14: Spring Break

Mar 15-21: 2 runs

Mar 22-28: 2 runs + Midterm: 22 runs

Mar 29-Apr4: 2 runs

April 5-11: 2 runs

April 12-18: 2 runs

April 19-24: 2 runs+ Final: 22 runs

April 26-28: 1 run

Total: 53 runs

Thank you for an amazing semester!

Wednesday, April 29, 2020

A Question for the Professor

When is our official last week for this site?

If we have already completed our final reports, do we finish out this week and post our final tallies for points based from Spring break onward? If so, when is that due?

If we have already completed our final reports, do we finish out this week and post our final tallies for points based from Spring break onward? If so, when is that due?

Frank Ramsey

The Man Who Thought Too Fast

Brilliant early pragmatist and Wittgensteinian, "atheist by the age of thirteen" and brother of the Archbishop of Canterbury... Frank Ramsey—a philosopher, economist, and mathematician—was one of the greatest minds of the last century. Have we caught up with him yet?By Anthony Gottlieb

“The world will never know what has happened—what a light has gone out,” the belletrist Lytton Strachey, a member of London’s Bloomsbury literary set, wrote to a friend on January 19, 1930. Frank Ramsey, a lecturer in mathematics at Cambridge University, had died that day at the age of twenty-six, probably from a liver infection that he may have picked up during a swim in the River Cam. “There was something of Newton about him,” Strachey continued. “The ease and majesty of the thought—the gentleness of the temperament.”

Dons at Cambridge had known for a while that there was a sort of marvel in their midst: Ramsey made his mark soon after his arrival as an undergraduate at Newton’s old college, Trinity, in 1920. He was picked at the age of eighteen to produce the English translation of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s “Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus,” the most talked-about philosophy book of the time; two years later, he published a critique of it in the leading philosophy journal in English, Mind. G. E. Moore, the journal’s editor, who had been lecturing at Cambridge for a decade before Ramsey turned up, confessed that he was “distinctly nervous” when this first-year student was in the audience, because he was “very much cleverer than I was.” John Maynard Keynes was one of several Cambridge economists who deferred to the undergraduate Ramsey’s judgment and intellectual prowess.

When Ramsey later published a paper about rates of saving, Keynes called it “one of the most remarkable contributions to mathematical economics ever made.” Its most controversial idea was that the well-being of future generations should be given the same weight as that of the present one. Discounting the interests of future people, Ramsey wrote, is “ethically indefensible and arises merely from the weakness of the imagination.” In the wake of the Great Depression, economists had more pressing concerns; only decades later did the paper’s enormous impact arrive. And so it went with most of Ramsey’s work. His contribution to pure mathematics was tucked away inside a paper on something else. It consisted of two theorems that he used to investigate the procedures for determining the validity of logical formulas. More than forty years after they were published, these two tools became the basis of a branch of mathematics known as Ramsey theory, which analyzes order and disorder. (As an Oxford mathematician, Martin Gould, has explained, Ramsey theory tells us, for instance, that among any six users of Facebook there will always be either a trio of mutual friends or a trio in which none are friends.)

Ramsey not only died young but lived too early, or so it can seem. He did little to advertise the importance of his ideas, and his modesty did not help. He was not particularly impressed with himself—he thought he was rather lazy. At the same time, the speed with which his mind worked sometimes left a blur on the page. The prominent American philosopher Donald Davidson was one of several thinkers to experience what he dubbed “the Ramsey effect.” You’d make a thrilling breakthrough only to find that Ramsey had got there first.

There was also the problem of Wittgenstein, whose looming example and cultlike following distracted attention from Ramsey’s ideas for decades. But Ramsey rose again. Economists now study Ramsey pricing; mathematicians ponder Ramsey numbers. Philosophers talk about Ramsey sentences, Ramseyfication, and the Ramsey test. Not a few scholars believe that there are Ramseyan seams still to mine.

Philosophers sometimes play the game of imagining how twentieth-century thought might have been different if Ramsey had survived and his ideas had caught on earlier. That exercise has become more entertaining with the publication of the first full biography of him, “Frank Ramsey: A Sheer Excess of Powers” (Oxford), by Cheryl Misak, a philosophy professor at the University of Toronto. Drawing on family papers and records of interviews conducted four decades ago for a biography that was never written, Misak tells a more colorful story than one might have thought possible so long after such a short life ended.

Ramsey’s father, Arthur, claimed that Frank, his eldest child, learned to read almost as soon as he could talk. His political sense was precocious, too. One day, little Frank told his mother, Agnes, that his younger brother, Michael, was, unfortunately, a conservative:

You see, I asked him, “Michael are you a liberal or a conservative?” And he said “What does that mean?” And I said “Do you want to make things better by changing them or do you want to keep things as they are?” And he said—“I want to keep things.” So he must be a conservative.

The two brothers later diverged in religious matters as well. Frank was an atheist by the age of thirteen; Michael entered the Anglican Church and became the Archbishop of Canterbury... (continues)

Tuesday, April 28, 2020

If you seek meaning

...you must answer this question:

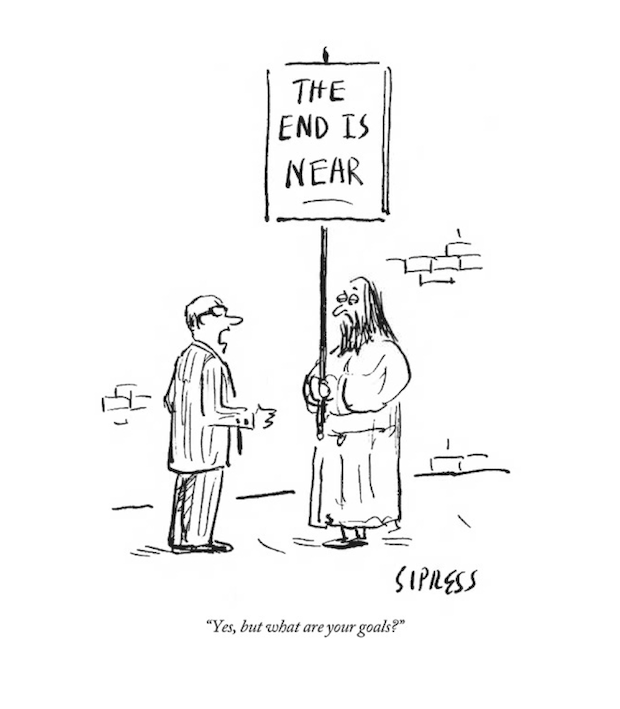

"Yes, but what are your goals?" But, a crucial addendum: don't just focus on your goals, pay close attention to the systems (the process, the routines, the environmental cues, the habits) that support them. Check out James Clear's Atomic Habits for an elaboration of the importance of system in supporting goals. “You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.” He converses about all this with Sam Harris here...

Today's dawn post: The end is near...

"Yes, but what are your goals?" But, a crucial addendum: don't just focus on your goals, pay close attention to the systems (the process, the routines, the environmental cues, the habits) that support them. Check out James Clear's Atomic Habits for an elaboration of the importance of system in supporting goals. “You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.” He converses about all this with Sam Harris here...

Today's dawn post: The end is near...

Monday, April 27, 2020

A Nice Dose of Vitamin D

I do not know what it is that makes me so happy to see the sun.

After all, I am an avid lover of the rain, but the sun today has made me feel optimistic and thus I wanted to speak briefly with you all.

The semester has been quite the adventure as the introduction of Coronavirus caused Americans to run around as a chicken does with its head chopped off. We of the saner bunch are at a loss of words.

To be short, I work in a grocery store and as small as it may be, seeing the slow but sure restock of perceived "emergency goods" has allowed me to hope that we will move past the destruction that occurred not long ago.

The governor is to reopen the state starting on the first. It will be slow, and social distancing will continue to be encouraged. I hope that people will adhere to these policies. Many of us are restless from being stuck in our homes while others of us have found our bliss and never want to leave. I admit that if I had no responsibilities elsewhere, I would be among the latter bunch. Being a homebody never hurt anybody.

I should admit that I consider myself to be a pessimist most of the time. Prepare for the worst is practically a life motto of mine, but I believe a little optimism could do some good for the present.

With that being said,

what are your thoughts? Do you see signs of slow recovery around you?

Since we only have a few more days left, I would love to hear this from you all.

After all, I am an avid lover of the rain, but the sun today has made me feel optimistic and thus I wanted to speak briefly with you all.

The semester has been quite the adventure as the introduction of Coronavirus caused Americans to run around as a chicken does with its head chopped off. We of the saner bunch are at a loss of words.

To be short, I work in a grocery store and as small as it may be, seeing the slow but sure restock of perceived "emergency goods" has allowed me to hope that we will move past the destruction that occurred not long ago.

The governor is to reopen the state starting on the first. It will be slow, and social distancing will continue to be encouraged. I hope that people will adhere to these policies. Many of us are restless from being stuck in our homes while others of us have found our bliss and never want to leave. I admit that if I had no responsibilities elsewhere, I would be among the latter bunch. Being a homebody never hurt anybody.

I should admit that I consider myself to be a pessimist most of the time. Prepare for the worst is practically a life motto of mine, but I believe a little optimism could do some good for the present.

With that being said,

what are your thoughts? Do you see signs of slow recovery around you?

Since we only have a few more days left, I would love to hear this from you all.

The End of God-Talk -- Final Report -- Updated May 5, 2020

Rice University's Dr. Anthony Pinn, a professor of religious studies and persistent scholar of African American religiosity in particular, offers a compelling presentation via The End of God-Talk: An African American Humanist Theology (2012).

This comes to me as no surprise. I've found Pinn to be both a rich resource and a challenging conversation partner--as for the latter, early phone talks with him were often frustrated by how much I didn't know, but also fruitful because they promised knowledge about religious alternatives. Moreover, when it's still common today for folks--black people included--to see an almost necessary association between being African American and being religious, I don't think I can overstate how much more impactful it was to hear an expression of atheism from Pinn.

Here's a snippet of Pinn that represents his relevance, I think, for secular communities.

Because it's so good, I was tempted to summarize God-Talk. I won't do that here, however. Instead, my final report is driven by the observation that several connections exist between Pinn's work and some key points we've covered in our course: the sources of secular thinking and the meaningfulness of human life.

First, though, I need to return to something I brought up in an earlier post. I mentioned there that Pinn's affinity for theological discourse--why he chose to do humanist theology rather than philosophy--had something to do with an identifiable traditional structure. By this, I'm referring to how theological discourse, especially the systematic variety, is usually preoccupied with addressing fundamental subjects in a way that is integrative, coherent, and comprehensive. For example, a typical Christian systematic theology might look like this when outlined:

I. God (theology proper)

II. Jesus (christology)

III. Humanity (theological anthropology)

IV. Sin/Salvation (soteriology)

V. Church (ecclesiology)

Or, if we let Joel Beeke break it down as an insider of Christianity:

(Note the video's emphasis on the sources or disciplines--biblical, historical, philosophical, experiential, etc.--used to do systematic theology. The subject of sources is something I'll come back to later.)

Pinn's presentation is not far off from the above structure. But there are some significant differences:

I. Community

II. Humanity

III. Wholeness

IV. Ethics

V. Celebration

Do you feel like you have a systematic secular worldview? What would you have to think about to get there? What do you notice about the order or arrangement of Pinn's system? What's first? Or how about what's absent? What do you think about the major inclusion of celebration, what Pinn also calls ritual? How does that fit into your understanding of nontheistic humanism?

(There's a lot to say about about the need for celebration in secular communities. For now, I'll settle on Fry's apt description of humanist ceremonies as a "contemporary way of satisfying a timeless need to bring significance to life's big changes" [1:45-1:55]. Humanists disregard this "timeless need" because of an undue fear of anything that resembles religion at our own peril.)

Beyond seeking a structural resemblance between humanist theology and systematic theology, by choosing theology over philosophy Pinn might also be expressing his position on humanism as both moral and religious. He is leery of what he suggests is a tendency to think of humanism as a purely scientific orientation, because science, while having great descriptive power, stops short of evaluating implications based on what ought or ought not to be. Science describes, but it doesn't prescribe. "[T]o interrogate the cultural implications and cultural pitfalls of . . . scientifically reasonable statement[s]" is among the "special abilities of theology," says Pinn (4). As for the religious-ness of humanism, Pinn has elsewhere explored African American religion as fundamentally a "quest for complex subjectivity" (2011). Rather than saddle you with the details, I'll emphasize that defining religion in this way reaches out to include non-theistic orientations such as humanism. So, if non-theistic humanism is a religion and theology is religion's articulation, then non-theistic humanism can--should?--have a theology. It's fascinating how, via an apparently slight vocabulary choice, Pinn makes such an important statement about the status of humanism! You might remember that Baggini talks a little about the religious-ness of humanism in the conclusion of Atheism: A Short Introduction (225-27).

What say you? Is secular humanism purely scientific? If science is our preferred mode of expression, how might this be a limitation? What do you think about seeing secular humanism as a religion? If it is, should its discourse be theology, then? Or would you prefer not to call humanism a religion and choose instead to follow Hagglund's use of "secular faith"? Remember that he distinguishes secular faith from "religious faith," because the former is "dedicated to persons or projects that are worldly and temporal," and "that [are] vulnerable to loss" (6). How about the portmanteau of "seculalogy" to name our secular theology ? Ha, ha!

(Note--with skepticism, I might add--the video's presumption of secular humanism's dominance in spaces of public education.)

At the start of our course, we dug into what it means to talk positively about life, meaning, and morality without a theistic belief. Wrestling with this was all the more necessary because it's taken for granted that, without theism, there are no durable sources for talking about these things. Baggini, however, talks about life having "its own answer to the question of why we should live" (152). Accordingly, we can look to the the details of our everyday, earthbound life to provide satisfactory answers to existential questions.

Pinn echoes this with a section in which he identifies the source material of his humanist theology and further distinguishes his work from traditional theology. In a word, Pinn's source material is "ordinary," primarily because Pinn's humanism "pays no allegiance to the idea of revealed materials that link the transcendent and human history" (9). There's no deference to supernaturally revelatory material that expresses the voice of God for all time and all people. To be fair, the Bible still has "some metaphorical or symbolic value," but it, and presumably other religious texts, "are no more significant and hold no greater meaning" than secular texts (ibid). The Hebrew Torah and Thoreau's Walden are essentially equivalent: both are human constructions that ruminate with earnestness on the existence of human beings, and we can learn from them. It should be said that privileged among Pinn's secular sources are African American literature, as well as other forms of what he calls "material culture," such as photographs and architecture (10-16).

Do you have a secular canon or a collection of source material that you privilege in your own life? If limited to three or five items, what would you include in that canon?

A final connection I'd like to make between Pinn's work and our course has to do with something many people find in the Bible: human meaningfulness. In Genesis, the first book of the Bible, there's a story of creation that describes human beings as made in the image of God (Gen. 1:27). Theologians for ages have interpreted this to mean, among many things, that humans are supernaturally special, that we have a soul, a God-given freedom, a divine spark, etc. Michael Ruse talks about this when he says, "We humans get our meaning and value from the fact that we are created by this God, out of love, for Him to cherish and for us to adore and obey Him."

For Pinn, however, and I'd gather for any atheist, exploring what it means to be human involves a move away from the ontological guarantees of the imago dei or "image of god" idea. The catch, as Ruse also points out, is that while giving this up means there's no idea of original sin, no fundamentally wicked deficiency in human nature to weigh us down; there's also no human approximation of divinity, no supernatural exception, and no eternal soul to elevate us. This can be a real downer, but it doesn't have to be. We can still find positive meaning in an understanding of human nature and worthiness that is not based on supernatural origins. Pinn's understanding of the self sees it as a "cultural construct" and a "materially embodied 'something' (that lives and dies)" (47). Pinn later describes how this focus on time and space "has more depth, more layers, more possibilities than formulations of salvation" (88). Pinn continues, in language not dissimilar from Hagglund's talk of finitude, "Lived life as embodied selves, in light of this and within the framework offered by nontheistic humanist theology, becomes recognized for its dynamic nature. And there is something elegant about this arrangement" (88). I couldn't agree more. There is something elegant, something gracious about how our finite lives provide opportunities for us to care about and be cared about. I've learned from Hagglund that this caring just wouldn't be the same--or wouldn't be caring at all--if we could count on some form of ourselves and our world lasting forever. That's cause to celebrate, right?

And, although we don't have the imago dei as an anthropological boost, we do have Carl Sagan's "star stuff," which never fails to blow me away!

"The cosmos is also within us. The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood. Everything we are made of was forged in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of star stuff. We are a way for the cosmos to know itself. Star stuff, contemplating the stars. Think of the possibilities." (6:26-7:10).

Well, there you have it, friends! It's been a wild ride this semester. I've learned a lot from each of you. Feel free to share any thoughts about this report.

Final Run Total Since COVID-19: 10

I estimate my overall run total to be between 20-30, but I am unsure because I failed to note my run count on the scorecard before we left for Spring Break. My apologies!

This comes to me as no surprise. I've found Pinn to be both a rich resource and a challenging conversation partner--as for the latter, early phone talks with him were often frustrated by how much I didn't know, but also fruitful because they promised knowledge about religious alternatives. Moreover, when it's still common today for folks--black people included--to see an almost necessary association between being African American and being religious, I don't think I can overstate how much more impactful it was to hear an expression of atheism from Pinn.

Here's a snippet of Pinn that represents his relevance, I think, for secular communities.

Because it's so good, I was tempted to summarize God-Talk. I won't do that here, however. Instead, my final report is driven by the observation that several connections exist between Pinn's work and some key points we've covered in our course: the sources of secular thinking and the meaningfulness of human life.

First, though, I need to return to something I brought up in an earlier post. I mentioned there that Pinn's affinity for theological discourse--why he chose to do humanist theology rather than philosophy--had something to do with an identifiable traditional structure. By this, I'm referring to how theological discourse, especially the systematic variety, is usually preoccupied with addressing fundamental subjects in a way that is integrative, coherent, and comprehensive. For example, a typical Christian systematic theology might look like this when outlined:

I. God (theology proper)

II. Jesus (christology)

III. Humanity (theological anthropology)

IV. Sin/Salvation (soteriology)

V. Church (ecclesiology)

Or, if we let Joel Beeke break it down as an insider of Christianity:

(Note the video's emphasis on the sources or disciplines--biblical, historical, philosophical, experiential, etc.--used to do systematic theology. The subject of sources is something I'll come back to later.)

Pinn's presentation is not far off from the above structure. But there are some significant differences:

I. Community

II. Humanity

III. Wholeness

IV. Ethics

V. Celebration

Do you feel like you have a systematic secular worldview? What would you have to think about to get there? What do you notice about the order or arrangement of Pinn's system? What's first? Or how about what's absent? What do you think about the major inclusion of celebration, what Pinn also calls ritual? How does that fit into your understanding of nontheistic humanism?

(There's a lot to say about about the need for celebration in secular communities. For now, I'll settle on Fry's apt description of humanist ceremonies as a "contemporary way of satisfying a timeless need to bring significance to life's big changes" [1:45-1:55]. Humanists disregard this "timeless need" because of an undue fear of anything that resembles religion at our own peril.)

Humanism -- Science or Religion?

Beyond seeking a structural resemblance between humanist theology and systematic theology, by choosing theology over philosophy Pinn might also be expressing his position on humanism as both moral and religious. He is leery of what he suggests is a tendency to think of humanism as a purely scientific orientation, because science, while having great descriptive power, stops short of evaluating implications based on what ought or ought not to be. Science describes, but it doesn't prescribe. "[T]o interrogate the cultural implications and cultural pitfalls of . . . scientifically reasonable statement[s]" is among the "special abilities of theology," says Pinn (4). As for the religious-ness of humanism, Pinn has elsewhere explored African American religion as fundamentally a "quest for complex subjectivity" (2011). Rather than saddle you with the details, I'll emphasize that defining religion in this way reaches out to include non-theistic orientations such as humanism. So, if non-theistic humanism is a religion and theology is religion's articulation, then non-theistic humanism can--should?--have a theology. It's fascinating how, via an apparently slight vocabulary choice, Pinn makes such an important statement about the status of humanism! You might remember that Baggini talks a little about the religious-ness of humanism in the conclusion of Atheism: A Short Introduction (225-27).

What say you? Is secular humanism purely scientific? If science is our preferred mode of expression, how might this be a limitation? What do you think about seeing secular humanism as a religion? If it is, should its discourse be theology, then? Or would you prefer not to call humanism a religion and choose instead to follow Hagglund's use of "secular faith"? Remember that he distinguishes secular faith from "religious faith," because the former is "dedicated to persons or projects that are worldly and temporal," and "that [are] vulnerable to loss" (6). How about the portmanteau of "seculalogy" to name our secular theology ? Ha, ha!

(Note--with skepticism, I might add--the video's presumption of secular humanism's dominance in spaces of public education.)

Secular Sources

At the start of our course, we dug into what it means to talk positively about life, meaning, and morality without a theistic belief. Wrestling with this was all the more necessary because it's taken for granted that, without theism, there are no durable sources for talking about these things. Baggini, however, talks about life having "its own answer to the question of why we should live" (152). Accordingly, we can look to the the details of our everyday, earthbound life to provide satisfactory answers to existential questions.

Pinn echoes this with a section in which he identifies the source material of his humanist theology and further distinguishes his work from traditional theology. In a word, Pinn's source material is "ordinary," primarily because Pinn's humanism "pays no allegiance to the idea of revealed materials that link the transcendent and human history" (9). There's no deference to supernaturally revelatory material that expresses the voice of God for all time and all people. To be fair, the Bible still has "some metaphorical or symbolic value," but it, and presumably other religious texts, "are no more significant and hold no greater meaning" than secular texts (ibid). The Hebrew Torah and Thoreau's Walden are essentially equivalent: both are human constructions that ruminate with earnestness on the existence of human beings, and we can learn from them. It should be said that privileged among Pinn's secular sources are African American literature, as well as other forms of what he calls "material culture," such as photographs and architecture (10-16).

Do you have a secular canon or a collection of source material that you privilege in your own life? If limited to three or five items, what would you include in that canon?

Meaningfulness of Human Life

A final connection I'd like to make between Pinn's work and our course has to do with something many people find in the Bible: human meaningfulness. In Genesis, the first book of the Bible, there's a story of creation that describes human beings as made in the image of God (Gen. 1:27). Theologians for ages have interpreted this to mean, among many things, that humans are supernaturally special, that we have a soul, a God-given freedom, a divine spark, etc. Michael Ruse talks about this when he says, "We humans get our meaning and value from the fact that we are created by this God, out of love, for Him to cherish and for us to adore and obey Him."

For Pinn, however, and I'd gather for any atheist, exploring what it means to be human involves a move away from the ontological guarantees of the imago dei or "image of god" idea. The catch, as Ruse also points out, is that while giving this up means there's no idea of original sin, no fundamentally wicked deficiency in human nature to weigh us down; there's also no human approximation of divinity, no supernatural exception, and no eternal soul to elevate us. This can be a real downer, but it doesn't have to be. We can still find positive meaning in an understanding of human nature and worthiness that is not based on supernatural origins. Pinn's understanding of the self sees it as a "cultural construct" and a "materially embodied 'something' (that lives and dies)" (47). Pinn later describes how this focus on time and space "has more depth, more layers, more possibilities than formulations of salvation" (88). Pinn continues, in language not dissimilar from Hagglund's talk of finitude, "Lived life as embodied selves, in light of this and within the framework offered by nontheistic humanist theology, becomes recognized for its dynamic nature. And there is something elegant about this arrangement" (88). I couldn't agree more. There is something elegant, something gracious about how our finite lives provide opportunities for us to care about and be cared about. I've learned from Hagglund that this caring just wouldn't be the same--or wouldn't be caring at all--if we could count on some form of ourselves and our world lasting forever. That's cause to celebrate, right?

And, although we don't have the imago dei as an anthropological boost, we do have Carl Sagan's "star stuff," which never fails to blow me away!

"The cosmos is also within us. The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood. Everything we are made of was forged in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of star stuff. We are a way for the cosmos to know itself. Star stuff, contemplating the stars. Think of the possibilities." (6:26-7:10).

Well, there you have it, friends! It's been a wild ride this semester. I've learned a lot from each of you. Feel free to share any thoughts about this report.

Final Run Total Since COVID-19: 10

I estimate my overall run total to be between 20-30, but I am unsure because I failed to note my run count on the scorecard before we left for Spring Break. My apologies!

Sunday, April 26, 2020

The Long Now

We're all pretty focused now on the short-term and this viral moment, but ultimately it's long-term thinking that will save us if anything does. I support the work of the Long Now Foundation to raise our consciousness on this point, and I love the way Neil Gaiman expresses how we close the gap between now and the long now. Tell your children stories, read and talk to them, let them know they and we have a future. "There is a tomorrow," as Greta said. Pass the baton.

The long now is measured in stories told a generation at a time. https://t.co/vB8B0ugrJB— Phil Oliver (@OSOPHER) April 26, 2020

Saturday, April 25, 2020

Final Report

I have been reading a book called Tribes by Sebastian Junger

https://www.twelvebooks.com/titles/sebastian-junger/tribe/9781455566389/

Junger's book looks at earlier societies, especially native Americans, and dissects elements of those societies that benefitted greatly from close-knit communities that had minimal social isolation. Humans being the pack animals that we are, benefit greatly from institutions, belief system, and cultural traditions that create a sense of belonging and togetherness that leads to people feeling like they are contributing rather than competing.

In this contemporary time of social isolation and distancing, one of our only real outlets for meaningful and safe socialization has come from the electronic devices. Junger's book predates this crisis, and he is very critical of electronic socialization, and is a huge advocate of in person contact and togetherness as opposed to the electronic surrogates that we have become accustomed to in our time.

Junger's focus on the importance of in person socialization and community got me to thinking about whether or not we can adequately socialize through the use of electronics. I'm somewhat skeptical that we can fulfill all the social needs of our species from behind a screen, and potentially hundreds or thousands of miles away from those who we are digitally communing with.

If our society is forced to come up with a new kind of normal with incredibly limited physical proximity and contact between individuals and the community, will people be able to build the familial and community bonds necessary to bind people together in a positive way? I am unsure as to whether the electronics we will be relying on for the foreseeable future can serve as an effective catalyst for prosocial behavior and attitudes.

Questions for the Class:

Do you think that electronic communication can effectively build relationships that can sustain communities and their group identity?

Will excessive isolation time that results from social distancing measures negatively affect people's propensity for pro social behavior?

Can people's mental health needs be met primarily through electronic means? Do you agree or disagree with Jugner's notion that in person brotherhood and socialization are necessary to create a sense of belonging and community within a society? Why or why not?

https://www.twelvebooks.com/titles/sebastian-junger/tribe/9781455566389/

Junger's book looks at earlier societies, especially native Americans, and dissects elements of those societies that benefitted greatly from close-knit communities that had minimal social isolation. Humans being the pack animals that we are, benefit greatly from institutions, belief system, and cultural traditions that create a sense of belonging and togetherness that leads to people feeling like they are contributing rather than competing.

In this contemporary time of social isolation and distancing, one of our only real outlets for meaningful and safe socialization has come from the electronic devices. Junger's book predates this crisis, and he is very critical of electronic socialization, and is a huge advocate of in person contact and togetherness as opposed to the electronic surrogates that we have become accustomed to in our time.

Junger's focus on the importance of in person socialization and community got me to thinking about whether or not we can adequately socialize through the use of electronics. I'm somewhat skeptical that we can fulfill all the social needs of our species from behind a screen, and potentially hundreds or thousands of miles away from those who we are digitally communing with.

If our society is forced to come up with a new kind of normal with incredibly limited physical proximity and contact between individuals and the community, will people be able to build the familial and community bonds necessary to bind people together in a positive way? I am unsure as to whether the electronics we will be relying on for the foreseeable future can serve as an effective catalyst for prosocial behavior and attitudes.

Questions for the Class:

Do you think that electronic communication can effectively build relationships that can sustain communities and their group identity?

Will excessive isolation time that results from social distancing measures negatively affect people's propensity for pro social behavior?

Can people's mental health needs be met primarily through electronic means? Do you agree or disagree with Jugner's notion that in person brotherhood and socialization are necessary to create a sense of belonging and community within a society? Why or why not?

If society does end up having to enact social distancing measures

for an extremely prolonged period of time, what other alternatives to

electronic socialization might be equally as safe but more effective during a situation like the current pandemic?

Final Scorecard

Charles Trent

Scorecard April 19-25

April 25 – Spinoza’s God – Comment

April 25 – Secular Buddhist Solitude – Comment

April 24 - Presentation on

"There is a God: How the World's Most Prominent Atheist Changed His

Mind" – Comment

April 24 – Why do you believe what you do –

comment

April 23 – Final Report (Patricia) – comment

April 25 – The Relevance of Philosophy –

comment

April 23 – Ask an Atheist – comment

April 23 – More Plague Literature - comment

SPINOZA'S GOD

When asked by a New York rabbi if he believed in God, Albert

Einstein replied “I believe in Spinoza’s God.” The full quote is “I believe in

Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the orderly harmony of what exists, not

in a God who concerns himself with the fates and actions of human beings.”

Baruch

de Spinoza, who used the name Benedictus for his scholarly writings, and was

called Bento by his friends (it means “blessed,”), is recognized as the first

modern philosopher, breaking fully from the ancient and medieval schools. His

views are found in his two major works, Tractatus

Theologico-Politicus, published anonymously in Latin in 1670, and Ethics, Demonstrated in Geometrical Order,

generally referred to as the Ethics, which

was first published posthumously in 1677. Tractatus

Theologico-Politicus was regarded as the most dangerous book of its time,

and is regarded as one of the most significant events in European intellectual

history. One critic said that it was “a book forged in hell,” written by the

devil himself.

Spinoza’s story is fascinating. He was a Portuguese Jew born

in Amsterdam in 1661. He was a brilliant student in Hebrew school, who was

excommunicated from the Jewish community and cursed at 23. Apparently, this did not bother him. He went about

his life, freed from constraint by the Jewish and Christian communities, living

simply, grinding optical lenses for support, and developing his philosophy.

Interestingly, his virtuous life style and suspected atheism confused people.

How can one be virtuous without God?

In the Ethics,

Spinoza used the Euclidian geometric method and form; i.e., definitions, axioms, and propositions, to demonstrate the

truth about God and the principles of the good life. It is most definitely not

as easy read, unless you’re an Einstein. It contains five parts, each building

on the others, in sum amounting to one argument about a proper philosophy of

life.

Before he can get to the ethics parts (parts 3, 4, and 5),

he must demonstrate man’s place in the world, and before he can do that, he

must demonstrate the nature of the world. In Part One, “Concerning God,” through

eight definitions, seven axioms, and thirty-six propositions, Spinoza presents

geometric proof of the existence of God as Nature. He begins with the concept

of Substance. The whole of the universe,

all that is, is but one substance. Substance is indivisible; it is only one

being. It was not caused, not created by some external source. Its cause was

immanent; it is self-caused, i.e., it

exists through the necessity of its existence; existence is its essence, its

essential attribute. Substance is that

which has no boundary, no limit. The universe in infinite; it cannot be limited

by anything else. There cannot be anything beyond the universe. This is what he

called God. His famous phrase, Deus sive

nature, “God, or nature,” is not used until Part Four, however. God did not

create the universe. God is not transcendental, not a being separate from his

creation, he is his creation.

In Part Two, through seven definitions, eight axioms, and

forty-nine propositions, Spinoza demonstrates the nature of minds and bodies. Substance

has infinite attributes, which are the essence of substance. We know only two, thought and extension, i.e., consciousness and material

existence. Finite things, like us, and everything else in the universe – tables

and chairs, mountains, planets – are simply modes of substance, modifications.

In finite things, extension and thought are caused. The only thing that does

not have an external cause is substance. Therefore, we are not separate

substances. We are simply different aspects of the one substance Spinoza calls

God or Nature. This is a very important point for his full argument. Man is not

separate from nature, man is a mode of nature. We are not a “kingdom within a

kingdom.” Everything that occurs in nature

is determined by the very essence of nature, its essential attributes. Everything

that occurs in nature, and we are in nature, is caused by finite physical

events, which in turn were caused by finite physical events, and so on to

infinity. But the fact that everything is determined does not exclude our

individual efforts, which are part of the causal process.

Most of the attention to Spinoza’s work is focused on Parts

One and Two. The remaining parts of the work demonstrate how we can, through

understanding nature and our part in it, achieve the Stoic virtue of

tranquility. We acquire virtue by understanding the causes and consequences of

our actions. With a life of reason, we gain clarity about the causal forces

that are determining our circumstances; the causal forces at work in us

physically and emotionally, and the causal forces at work in the world around

us, as all a part of the one all-inclusive substance. It is by understanding

the causal mechanisms of nature, and accepting them as uncontradictable, that

we gain power to act and control our emotions. Acceptance brings peace of mind.

Virtue, the power of living a life in accordance with reason, is its own

reward.

Recommended reading:

Spinoza, Benedictus de. The

Ethics of Spinoza: the Road to Inner Freedom. Carol Pub. Group, 1995. (This

version of the Ethics is edited by D. D. Runes and is very much easier to read

that other more direct translations.)

Lloyd, Genevieve. Routledge

Philosophy Guidebook to Spinoza and the Ethics. Routledge, 2010. (An

excellent book for understanding Spinoza.)

Goldstein, Rebecca. Betraying

Spinoza: the Renegade Jew Who Gave Us Modernity. Nextbook, 2006. (More

understanding about the man and the basis for his philosophy.)

Nadler, Steven M. A

Book Forged in Hell: Spinozas Scandalous Treatise and the Birth of the Secular

Age. Princeton University Press, 2014. (Popular book about Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, Theological-Political

Treatise.)

Discussion questions:

1. If you don’t believe in an anthropomorphic god, does

Spinoza’s God appeal to you?

2. Do you think you are part of nature, or apart from

nature?

3. Do you find it comforting to see yourself as part of a

great inclusive one, or disturbing to think that you not somehow special with a

personal god who knows and loves you?

4. How does seeing yourself as a part of nature affect the

idea that God has given humanity dominion over all the earth?

5. If you accept the idea that God is one all-inclusive substance,

of which you are a modification, does that give you a greater identification

with all the other modifications? E.g.,

would you be more empathetic with the other modifications in nature, say air

and water, that are being harmed by your activities?

Secular Buddhist solitude

We're all together in this, it's true. But we're also all alone in this, even in a house full of others.— Krista Tippett (@kristatippett) April 25, 2020

This week's @onbeing is an offering towards living the difference between loneliness & isolation or a life-giving solitude. https://t.co/FNYgzqygE5

The relevance of philosophy

Philosophers are advising governments on #coronavirus strategy because 'a systemic crisis...needs to be dissected from every angle'. This is not just about direct mortality rates #philosophy https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/german-humanities-scholars-enlisted-end-coronavirus-lockdown …

See Ian Dyball's other Tweets

How to Spot Bullshit: A Primer by Princeton Philosopher Harry Frankfurt http://www.openculture.com/?p=1019510 https://twitter.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1253679654734573570 …

15 people are talking about this

Friday, April 24, 2020

Presentation on "There is a God: How the World's Most Prominent Atheist Changed His Mind"

I decided to read Antony Flew's book "There is a God: How the World's Most Notorious Atheist Changed His Mind". This book was particularly interesting because I hear so much more about religious individuals turning to Atheism but I don't hear so much of the reverse occurring.

Let me know what you think, do any of Flew's arguments speak to you?

Why do you believe what you do? Run some diagnostics on it

Thanks again, Ed.

Many of the beliefs that play a fundamental role in our worldview are largely the result of the communities in which we’ve been immersed. Religious parents tend to beget religious children, liberal educational institutions tend to produce liberal graduates, blue states stay mostly blue, and red ones stay mostly red. Of course, some people, through their own sheer intelligence, might be able to see through fallacious reasoning, detect biases and, as a result, resist the social influences that lead most of us to belief. But I’m not that special, and so learning how susceptible my beliefs are to these sorts of influences makes me a bit squirmy.

Let’s work with a hypothetical example. Suppose I’m raised among atheists and firmly believe that God doesn’t exist. I realise that, had I grown up in a religious community, I would almost certainly have believed in God. Furthermore, we can imagine that, had I grown up a theist, I would have been exposed to all the considerations that I take to be relevant to the question of whether God exists: I would have learned science and history, I would have heard all the same arguments for and against the existence of God. The difference is that I would interpret this evidence differently. Divergences in belief result from the fact that people weigh the evidence for and against theism in varying ways. It’s not as if pooling resources and having a conversation would result in one side convincing the other – we wouldn’t have had centuries of religious conflict if things were so simple. Rather, each side will insist that the balance of considerations supports its position – and this insistence will be a product of the social environments that people on that side were raised in.

The you-just-believe-that-because challenge is meant to make us suspicious of our beliefs, to motivate us to reduce our confidence, or even abandon them completely. But what exactly does this challenge amount to? The fact that I have my particular beliefs as a result of growing up in a certain community is just a boring psychological fact about me and is not, in itself, evidence for or against anything so grand as the existence of God. So, you might wonder, if these psychological facts about us are not themselves evidence for or against our worldview, why would learning them motivate any of us to reduce our confidence in such matters? (continues)

Miriam Schoenfield is associate professor in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Texas at Austin.

"Overcoming Partisan Politics" at the Frist, via Zoom

A note from Vandy philosopher (and our Lyceum speaker last Fall) Robert Talisse, if anyone's interested:

A lot has happened since I first let those of you who are in Nashville know about the gallery talk I was to give at the Frist Art Museum in connection with their Flag Exchange exhibit. The talk is still on, but the date has changed, and it has been moved to a virtual format (so now you don’t have to be in Nashville to attend!).

Here are the new details. I’m doing a Frist Online Gallery Talk about “Overcoming Partisan Politics” over Zoom on Friday, May 8th at 3:00pm.

I hope you can join us. More information, including details about registering and joining the Zoom session, is at the link below. The event is free and open to all, so feel free to share:

Cheers, and stay safe, —RBT

____________________________

Dr. Robert Talisse

W. Alton Jones Professor of Philosophy

W. Alton Jones Professor of Philosophy

Philosophy Department

Vanderbilt University

PMB 406319

2301 Vanderbilt Place

Nashville, TN 37240-6319

Quiz Apr 28

[audio file removed]... The End is Near

1. What (beyond basic biology) accounts for the different species natures that distinguish humans from other animals? 135

2. About what does Ruse say Sartre was right and wrong, respectively? 142

3. "What or who is to stop me" from behaving badly? 151

4. What is the meaningful life, according to Ruse, and by what three things of great worth is it informed? 158-9

5. Why is Ruse ultimately an agnostic about meaning? 169

DQ

1. What (beyond basic biology) accounts for the different species natures that distinguish humans from other animals? 135

2. About what does Ruse say Sartre was right and wrong, respectively? 142

3. "What or who is to stop me" from behaving badly? 151

4. What is the meaningful life, according to Ruse, and by what three things of great worth is it informed? 158-9

5. Why is Ruse ultimately an agnostic about meaning? 169

We can be grateful to be alive and we can enjoy the surge of energy in the struggle for moments of meaning and light. In this way, though we may not always make love to life or prevail over force and circumstance, we can at least glory in the effort and feel fully alive.

DQ

- Do you agree that Sartrean atheist existentialism describes "a bleak world indeed"? 134 Is that due to its commitment to atheism, or to something else?

- Are the individual differences between individual humans sufficient to warrant the claim of different human natures?

- Are biology and culture ("nature and nurture") equally responsible for shaping human nature? How would you characterize the relation between them?

- In what sense are we, or are we not, selfish genes? Or selfish beings?

- Was Hume right about the relation between duty and passion? 146

- What would be on your personal list of great worth that differs from Ruse's?

- Is mysterianism a satisfactory view of consciousness? 168

- What's your stance on meaning: believer, disbeliever, agnostic, other?

- COMMENT: "Life here and now can be fun and rewarding, deeply meaningful." 170

- COMMENT on the Lachs quote (above).

- COMMENT on the Pythons quote (below).

Well, it's nothing very special. Uh, try and be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try and live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations...

Thursday, April 23, 2020

FINAL REPORT

Hey guys!

This is my final report where I discussed the manipulation of Religion.

I hope you guys enjoy, and once again I ask for your patience with my

amateur editing skills.

Questions to ponder:

What are your thoughts on the topic?

How do you feel about the relationship between Religion and Humanity?

Do you believe that religion's grip is lessening on newer generations?

Do you like Hunchback of Notre Dame?(Joke Question, but feel free to answer)

Let me know in the comments!

This is my final report where I discussed the manipulation of Religion.

I hope you guys enjoy, and once again I ask for your patience with my

amateur editing skills.

Questions to ponder:

What are your thoughts on the topic?

How do you feel about the relationship between Religion and Humanity?

Do you believe that religion's grip is lessening on newer generations?

Do you like Hunchback of Notre Dame?(Joke Question, but feel free to answer)

Let me know in the comments!

Ask an Atheist

Hello Everyone, I hope you all are staying safe and healthy.

In honor of last week -- April 16th to be exact -- (allegedly) being "Ask an Atheist" Day - I wanted to share some of the questions in response after a friend of mine posted about it on Facebook-

1. What made you come to this conclusion?

2. What if you're wrong?

3. Why do you still celebrate holidays?

4. Do you believe in any higher power at all? Intelligent design? Etc? Or just nothing?

5. What if you're wrong?

6. What is your personal take of what happens when you die?

I am an Atheist so I will post some of my responses in the comments. And also, if anyone who is religious has any other questions - let's here 'em.

In honor of last week -- April 16th to be exact -- (allegedly) being "Ask an Atheist" Day - I wanted to share some of the questions in response after a friend of mine posted about it on Facebook-

1. What made you come to this conclusion?

2. What if you're wrong?

3. Why do you still celebrate holidays?

4. Do you believe in any higher power at all? Intelligent design? Etc? Or just nothing?

5. What if you're wrong?

6. What is your personal take of what happens when you die?

I am an Atheist so I will post some of my responses in the comments. And also, if anyone who is religious has any other questions - let's here 'em.

More "Plague Literature" -- Yes, It's a Genre!

Well, after being encouraged by Dr. Oliver's sharing of words from Camus' The Plague, I fell down the rabbit hole of stories, tales, and episodes that are set within a world threatened by widespread disease. I won't bother you with all that I found; just one.

Here's how The Conversation reported on the contemporary relevance of this centuries-old piece of literature:

Following the 1348 Black Death in Italy, the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio wrote a collection of 100 novellas titled, “The Decameron.” These stories, though fictional, give us a window into medieval life during the Black Death – and how some of the same fissures opened up between the rich and the poor. Cultural historians today see “The Decameron” as an invaluable source of information on everyday life in 14th-century Italy.

. . . . . . . .

Here's how The Conversation reported on the contemporary relevance of this centuries-old piece of literature:

Following the 1348 Black Death in Italy, the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio wrote a collection of 100 novellas titled, “The Decameron.” These stories, though fictional, give us a window into medieval life during the Black Death – and how some of the same fissures opened up between the rich and the poor. Cultural historians today see “The Decameron” as an invaluable source of information on everyday life in 14th-century Italy.

. . . . . . . .

. . . Boccaccio describes the rich secluding themselves at home, where they enjoy quality wines and provisions, music and other entertainment. The very wealthiest – whom Boccaccio describes as “ruthless” – deserted their neighborhoods altogether, retreating to comfortable estates in the countryside, “as though the plague was meant to harry only those remaining within their city walls.”

Meanwhile, the middle class or poor, forced to stay at home, “caught the plague by the thousand right there in their own neighborhood, day after day” and swiftly passed away. Servants dutifully attended to the sick in wealthy households, often succumbing to the illness themselves. Many, unable to leave Florence and convinced of their imminent death, decided to simply drink and party away their final days in nihilistic revelries, while in rural areas, laborers died “like brute beasts rather than human beings; night and day, with never a doctor to attend them” (read more).

This sounds a lot like this class' criticism of the today's ultra-wealthy, criticism that rightly asked, "All in it Together?" Maybe this is a another incidental benefit of pandemics, though. They expose the persistent societal flaws and inequalities we spent most of time disguising. So, although we might not take sufficient action to address these problems, we'll find it more difficult to lie to ourselves about their existence. That's something, right? What do you think?

Also, check out this interesting StoryMaps project that was inspired by the contemporary relevance of The Decameron:

The story map "The Decameron in the Time of Coronavirus" can be accessed directly here:

Last Call

Tonight I will host the last Happiness Hour for this semester. Please join me on Zoom. Let's raise a glass to Phil. After all, it's not often you can take a course in atheism. I suggest we share with him a bit of what we got out of the course.

Meeting ID: 903 806 2486

6:10 p.m., after the Huntley Brinkley Report

Meeting ID: 903 806 2486

6:10 p.m., after the Huntley Brinkley Report

Ann Druyan & Carl Sagan

Fascinating wide-ranging conversation with Cosmos co-creator, Carl Sagan's widow Ann Druyan. Half an hour in, they discuss concepts of an afterlife very much in the spirit of This Life and the notion that meaning comes to us precisely when we acknowledge that we're finite beings who've learned to embrace and treasure the transitory time of our lives. If you want meaning, Carl said, do something meaningful. She also talks about why she and Carl, both atheists, resisted militant atheism.

SCIENCE SALON # 112

Michael Shermer with Ann Druyan — Cosmos: Possible Worlds

In this sequel to Carl Sagan’s beloved classic and the companion to the hit television series hosted by Neil deGrasse Tyson, the primary author of all the scripts for both this season and the previous season of Cosmos, Ann Druyan explores how science and civilization grew up together. From the emergence of life at deep-sea vents to solar-powered starships sailing through the galaxy, from the Big Bang to the intricacies of intelligence in many life forms, Druyan documents where humanity has been and where it is going, using her unique gift of bringing complex scientific concepts to life. With evocative photographs and vivid illustrations, she recounts momentous discoveries, from the Voyager missions in which she and her husband, Carl Sagan, participated to Cassini-Huygens’s recent insights into Saturn’s moons. This breathtaking sequel to Sagan’s masterpiece explains how we humans can glean a new understanding of consciousness here on Earth and out in the cosmos — again reminding us that our planet is a pale blue dot in an immense universe of possibility. Druyan and Shermer also discuss:

- how to write a script for a television series

- her 20 years with Carl Sagan and what their collaboration meant

- how she dealt with her grief after Carl’s death (and how any of us can deal with such pain)

- who the Voyager records were really for

- Breakthrough Starshot

- science and religion

- God and morality

- free will and determinism

- the hard problem of consciousness

- the Fermi Paradox (where is everybody?)

- women in science

- how we can eventually settle on other worlds, and

- how to reach the stars … and beyond.

Ann Druyan is a celebrated writer and producer who co-authored many bestsellers with her late husband, Carl Sagan. She also famously served as creative director of the Voyager Golden Record, sent into space 40 years ago. Druyan continues her work as an interpreter of the most important scientific discoveries, partnering with NASA and the Planetary Society. She has served as Secretary of the Federation of American Scientists and is a laureate of the International Humanist Academy. Most recently, she received both an Emmy and Peabody Award for her work in conceptualizing and writing National Geographic’s first season of Cosmos.

Listen to Science Salon via Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Play Music, Stitcher, iHeartRadio, and TuneIn.

CARL SAGAN

The Possibility of Life in the Universe

This lecture by Carl Sagan was delivered in 1979 to a packed university auditorium in Colorado Springs, Colorado. It reflects the science of that time, and in the Q&A Dr. Sagan addresses the related claim that not only is there definitive proof for the existence of Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence in the cosmos, ETIs have visited Earth. Dr. Sagan’s exquisite deconstruction of such claims is a classic exercise in skeptical and critical thinking.

Courtesy of Ann Druyan. All rights reserved.

Follow the Official Carl Sagan Fan Page on Instagram @saganism

Follow the Official Ann Druyan Fan Page on Instagram @druyanism

Follow the Official Carl Sagan Fan Page on Instagram @saganism

Follow the Official Ann Druyan Fan Page on Instagram @druyanism

Recorded by Frederick Malmstrom.

Audio Processing by Michael Aisner.

Thank you to Frederick Malmstrom for recording this lecture in 1979 and for sending it to us along with this photograph of Jupiter autographed by Carl Sagan (below).

Audio Processing by Michael Aisner.

Thank you to Frederick Malmstrom for recording this lecture in 1979 and for sending it to us along with this photograph of Jupiter autographed by Carl Sagan (below).

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)