Some questions raised earlier in our class about the relationship between African Americans and atheism made me rethink my original choice of Anthony Pinn's systematic presentation of a black humanistic theology (a book-length project that I still totally recommend). Instead, I now think it's worth taking a step back toward the simpler but no less important effort of affirming the real existence of black "irreligiosity"--that is, the absence of strong religious feeling or belief among African Americans--throughout history. This effort is compellingly made by a recent publication by Dr. Christopher Cameron entitled, Black Freethinkers: A History of African American Secularism (2019).

|

| Cameron has recently given talks sponsored by the American Humanist Association about his book. |

Cameron certainly covers a lot of history in this text, from slavery up to our contemporary moment, but the thesis guiding his exploration is fairly straightforward. He argues that the historical and, more generally, scholarly record is skewed toward black belief, not simply because there are numerically more black theists than atheists but because of the "assumption that atheism and other forms of nonbelief are the preserve of whites" (ix). A related assumption is "that black people are naturally religious and that the black church has always been at the center of the black community" (x). (Some might be disappointed to hear that there is in fact no religious "bone" with which all black people are born.) Cameron's project is aimed at upsetting these assumptions, and it serves as both a historiographic intervention and an advance in the re-theorization of black (ir)religion away from the dominance of Christianity.

As said, Cameron covers a lot of history. I want to focus on three of the several periods he covers.

Slavery, Cameron emphasizes, was an immense experience of suffering that challenged the idea of God among black people. Not every African American responded to their plight by seeking refuge, rescue, or escape from any god--Christian or otherwise. In fact, it is well-documented that Christian missionaries worried about the noticeable trend of black alienation from religion because of slavery. That slavery made some African Americans less likely to believe in any god became an argument in abolitionist discourse (3-4, 10-11). Among enslaved persons whose belief in God was challenged by slavery, Cameron counts Frederick Douglass. Douglass certainly used Christian rhetoric in his prominent speaking and writing endeavors, but it seems that his personal conception of god was distant from traditional understandings. This "heterodoxy" was enough for Cameron to consider Douglass a freethinker, if the atheist label is too hard a sell. Cameron recounts an episode during which Douglass, while at an American Anti-Slavery Society meeting, provoked criticism for thanking human beings rather than just God. Douglass said, "It is only through such men and such women that I can get a glimpse of God anywhere" (32, italics added).

|

| Frederick Douglass, a black freethinker, said once, "I bow to no priests either of faith or of unfaith. I claim as against all sorts of people, simply perfect freedom of thought" (32). |

The Civil Rights era is especially problematic when it comes to black religiosity. Typically, the movements against racial oppression, being prominently led by religious leaders like MLK, get broadly brushed as Christian. In truth, many African Americans of a variety of religious and non-religious persuasions worked with and alongside these movements. Civil Rights was no more exclusively Christian (or theist) than it was exclusively black. Cameron supports this alternate take by emphasizing the involvement of Black Power personalities like Stokely Carmichael, Lorraine Hansberry, and James Forman. Forman rejected theism outright and described what he took to be its negative pacifying effects on African Americans (120). Although Carmichael was a Marxist atheist, he took a more diplomatic and pragmatic approach. He felt that being an influential activist meant that "any talk of atheism and the rejection of God just wasn't gonna cut it" (131-32). For someone like Hansberry, whose artistic focus perhaps gave her a bit more freedom and openness, it was possible to express atheism--still quite taboo in black communities--in her characters. Beneatha in A Raisin in the Sun (for an immediately relevant scene, skip to view 29:25-31:00) is an outstanding example.

Describing

Beneatha as “me, eight years ago,” Hansberry openly claimed atheism, while

respecting and empathetically accommodating religious imagination: “this is one

of the glories of [humanity], the inventiveness of the human mind and the human

spirit; whenever life doesn’t seem to give an answer, we create one. And it

gives us strength. I don’t attack people who are religious at all . . . I

rather admire this human quality to make our own crutches as long as we need

them. The only thing I am saying is that once we can walk,

you know—then drop them” (152). Lorraine, I couldn't agree more!

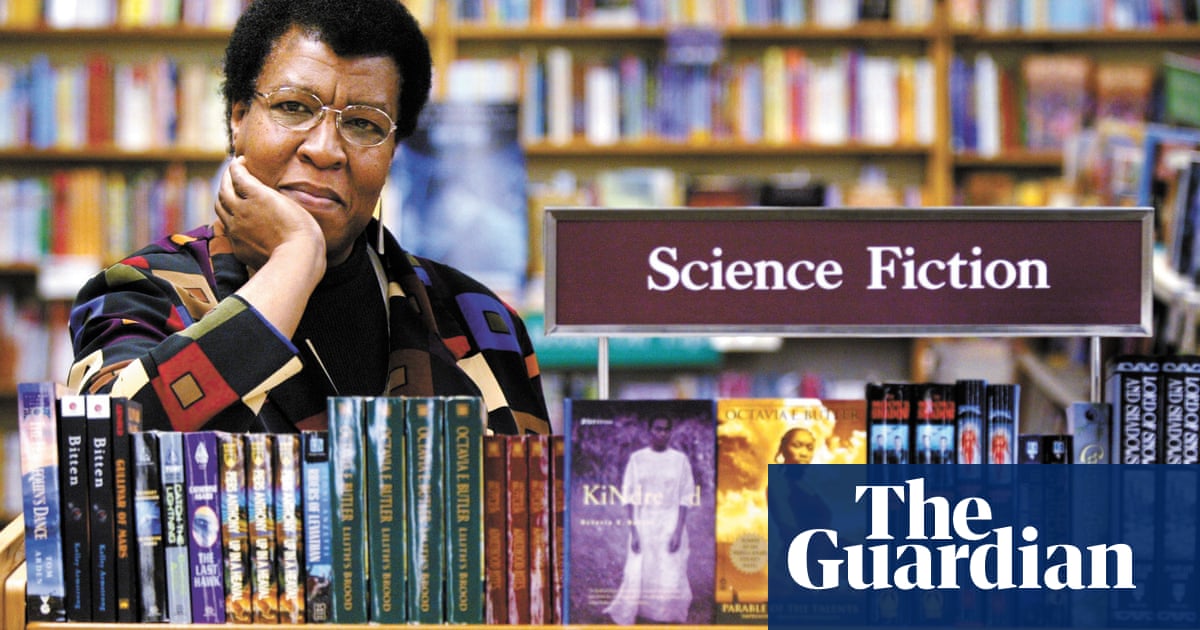

As more recent examples of black freethought and atheism, Cameron concludes his book with figures such as critically acclaimed but woefully underappreciated science fiction author Octavia Butler and the more well-known Alice Walker. Both incorporated religiously deviant ideas into their literature and spoke openly about their beliefs. Walker was even awarded the 1997 prize for Humanist of the Year (165-66, 169).

| |

|

Cameron further distinguishes this most recent period by describing the growth of institutional and organizational support for black irreligion. Organizations like African Americans for Humanism, Black Atheists of American, and Black Nonbelievers, are steadfastly working to ensure that African Americans who choose atheism have soft places to land outside of the traditional church, which yet functions as one of the most identifiable sources of social support for black people.

Hopefully, with the work of Cameron and others, we can attend with greater sensitivity to the presence black freethought and atheism--both of yesteryear and today.

Hopefully, with the work of Cameron and others, we can attend with greater sensitivity to the presence black freethought and atheism--both of yesteryear and today.

Below is a video of another talk given by Dr. Cameron. Enjoy!

Questions:

What is the thesis or main idea driving Cameron's historical project?

Who are two figures that exemplify black freethought or atheism?

Discussion:

How have you understood the relationship between black identity and religion? What would you say about how it is popularly represented?

How does the experience of Beneatha from A Raisin in the Sun resonate (or not) with your own experience of expressing atheism at home?

The struggle for greater institutional and organizational support for black atheism raises this issue also for atheists of every background. How can we do better to provide community for those seeking alternatives to "church"?

What is the thesis or main idea driving Cameron's historical project?

Who are two figures that exemplify black freethought or atheism?

Discussion:

How have you understood the relationship between black identity and religion? What would you say about how it is popularly represented?

How does the experience of Beneatha from A Raisin in the Sun resonate (or not) with your own experience of expressing atheism at home?

The struggle for greater institutional and organizational support for black atheism raises this issue also for atheists of every background. How can we do better to provide community for those seeking alternatives to "church"?

Really enjoyed this presentation, thanks for sharing this info. I have a few new authors on my list to read!

ReplyDeleteThanks, Jamil. Enjoyed and learned from your presentation.

ReplyDeleteLet us know if you discover anything about Hubert Harrison, a figure I'm sure we should all know more about.